|

Scrums and mauls are the two great dominance contests within the game of rugby. Marked superiority in either of these forms of engagement can affect the morale of both teams in a way that a corresponding supremacy at say the lineout does not.

Forward packs spend countless hours developing scrum technique but very much less attention is given to the maul, particularly in a defensive situation. Scrums are also elaborately structured whereas mauls tend to be chaotic. To a large extent this is due to the relative extent to which the two are regulated by the Laws of Rugby. Law 20, relating to the scrum, comprises three times as many pages as Law 17 pertaining to the maul.

Unlike the scrum, the Laws are largely silent on what players can do in the maul. Within the maul itself the most relevant clauses are that "Players joining a maul must have their heads and shoulders no lower than their hips" (17.2 (a)); they "must endeavour to stay on their feet" (17.2 (d)); and "A player must not intentionally collapse a maul" (17.2 (e)). Thus there remains considerable latitude for creativity.

One very marked difference between the two contests is that in the scrum either pack, whether having the feed or not, has the opportunity to establish dominance and drive the other pack back. By contrast it is very rare in the maul for the side not in possession to gain significant ground. This is largely due to the fact that the team with the ball is able to surreptitiously transfer the ball laterally from hand to hand so that the push from their opponents bypasses the ball-carrier, allowing him to be driven forward more or less unimpeded.

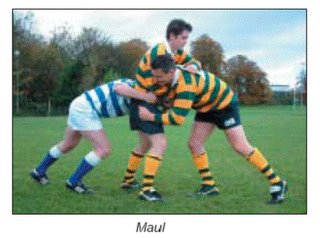

I believe that players can be trained to maul much more effectively and the secret is body height. Note the photo reproduced from the International Rugby Board's online version of the Laws of Rugby. It is intended to show the player involvements necessary for a maul to be formed. But it is also very instructive in illustrating body heights typically adopted in the maul. The ball carrier is standing upright, making no attempt to crouch. His team mate in attempting to seal off the ball has his shoulder at chest height of the ball-carrier. Their opponent has bound on the ball-carrier at waist height. None of these players have their legs positioned to exert an effective forward shove.

The body height adopted by the first players engaging from each team usually defines the height of their side of the ensuing maul. Subsequent players typically bind against the buttocks of the players in front of them. Players arriving at a maul tend to simply bend at the waist when joining the contest.

The body height

of rugby players in mauls tends to be very much higher

than in scrums. High body positions are inefficient

for generating forward momentum. There would be advantages

in training players to pack at thigh height rather

than waist height. Not only are they likely to gain

dominance in the maul, but the practice of adopting

biomechanically superior body positions is energy-conserving

over the course of a game.

Compare the likely height of this maul with the body height of the same players in a scrum situation. It can be confidently anticipated that body heights would be at least 300mm lower in a scrum than in a maul.

If the defending player in the photo were to bind around the thighs of his opponent rather than the waist, he would create a platform for his team mates to bind at something close to scrummaging height. Each of the players is then likely to have optimal hip and knee joint angles for generating forward momentum. It might even be advantageous for players to adopt the second-rower's technique of binding between the thighs of the player in front, whether team mate or foe. The one essential requirement is that players packing low secure a very firm grip to avoid being penalised for going to ground.

While front row players in the scrum are prohibited from "lifting or forcing an opponent up" (20.8 (i)), there is no corresponding restriction in relation to mauls. Although lifting is treated as "dangerous play" in the scrum, it does not have the same connotation in the maul where players are bound in an unstructured way and not confined or compressed as in the scrum. With his shoulder under his opponent's buttocks a player is ideally placed to drive up, forcing the opponent to give ground.

While mauls are often formed in an unstructured way, many of them emerge from static engagements such as the lineout or where the ball is being contested after a tackle. In such a situation a well-drilled team would have the opportunity to rapidly adopt a pseudo-scrum formation and drive forward. Not only are they likely to gain advantage in that particular maul, but the practice of adopting biomechanically superior body positions will undoubtedly be energy-conserving over the course of a game.

This article also appears on the MyoQuip Blog

website where Nick Tatalias has commented:

"I agree wholeheartedly that body position on the defensive Maul is wrong, good counter maul works well when the defending team launch and engage the push before the offensive team have chance to set up. These tactics were used by New Zealand against England last year and this prevented the maul from forming at line out time when England where on attack deep in Kiwi territory resulting in New Zealand's short manned defensive stand. However in these structured counter moves a much better body position was used by the defence, but this was not always the case even in that game. Co-ordinated efforts will also prevent offensive shifting of the point of attack.

"Secondly when engaging the opposition as in the photograph the tendency of players to turn their backs to "secure" the ball places them in the disadvantageous strength position that you discuss. If the player were instead to drive forward into his defender aiming to hit at waist height with his shoulder and the support player were to attempt to bind on to the defender and drive in the upward direction then as the maul beggins the movement would be moving in the direction of the ball carrier, the ball would also remain safely out of the defensive players grasp. Any additional attacking players joining the maul attack and bind onto the maul next to the ball carrier and the ball carrier can then move in behind the two support player while still driving the ball forward. This type of (initially) double team would need to be well drilled and co-ordinated to prevent isolation of the ball carrier. The defensive side should similarly endeavour to engage the attacking player quickly trying to isolate the ball carrier in a double team to drive him backward.

"In both situations the player who makes contact lower than his opposite player will win the contact. Driving up and through the oppositio0n player will reduce that players efficiency in counter pushing and his ability to resist the drive. Using the ScrumTruck should help to strengthen the players for this type of contact and if the unit were to be able to set at say 20 to 30 degrees above flat then this driving technique would be conditioned in a specific way. Some of the run blocking skills taught in American football could be modified and made appropriate for rugby. These essentially entail the player squaring up facing the try line with a low body position and driving with very strong and explosive leg drive using small choppy steps. As success of this technique increased players would also be less inclined to turn their backs, additionally better conditioned players would be less fearful of the contact and this aspect of the game can easily develop into a game winner."

The article also appears on the Rugger Bore site where the following two comments were posted:

flyer wrote:

"Good article and I guess it should be the ideal of every coach teaching mauling to encourage low body height. I particularly liked the point made about using a 2nd-rowers binding technique. It would be a very sound way to increase the bind strength in a maul, plus it should help lock your shoulder against the player in front's buttock."

shambles wrote:

"This is a very technical and interesting article.

"I would agree that there is room for improvement in the body position of defensive players joining a maul in order to gain more effective shoving power.

"However, the author correctly recognizes that the more upright and less structured form of a defensive maul exists by necessity; the team in possession and going forward has the opportunity to move the ball between players and vary the line of the drive. Thus the defending maulers are forced to adopt a more upright and loosely bound defense in order to see and respond to the changing line of attack. A lower, tightly bound defensive maul may well drive the original ball carrier back, but it could make it all too easy for the attacking team to offload laterally and drive up the fringes. Defending maulers that are tightly bound with low body position would find it more difficult to see the change of line and could furthermore find themselves over committed in the drive, perhaps going several yards past the ball carrier and off their feet.

"In short, I would agree on room for improvement in the body position of defending maulers. However, coaches wishing to improve the shoving power of their defensive maul should also place emphasis on the following:

"- The opportunity for effective drive in defensive mauling lies with the first two defenders ie. before support has arrived in numbers for the ball carrier, allowing him to offload and change the line of the drive.

"- A lower body position is necessary but with head up to detect the changing line of attack (unlike more head down scrummaging formation).

"- well drilled and considered decision making on numbers of driving players versus tacklers at the fringes is essential.

"- good communication between defensive maulers and in particular the scrum half regarding the changing line of attack is also essential."

Additional comments are invited. Please email to Bruce Ross

(This article may be reproduced so long as appropriate acknowledgement is made of author and source.)

For

up-to-the-minute information about Myoquip and discussion of

strength-related issues visit the MyoQuip

Blog

Email MyoQuip for

quotes and other product information

Please bookmark this site and come back

often

|